Wikipedia – one version of the truth?

It’s probably not unfair to say that law firms and the British struggle with Wikipedia.

Brits often seem obsessed with opinions and not facts at the moment. Some people call it a post-truth world, others say the truth has simply been put on hold. Ironically, we can’t even agree on that. One definite fact is that in the UK, our use of the world’s most trusted information source Wikipedia is only one-third of France’s usage (we have similarly sized populations, according to Wikipedia: 66.5m and 67.02m, respectively).

Yet law firms struggle with Wikipedia for a different reason: they don’t get to hold the pen.

Of the top 50 law firms by revenue (according to The Lawyer’s 200)

- 42 of them don’t even have a Wikipedia page.

- 7 of those who do have Wikipedia entries have minor page violations

- 11 of the firms who do have major page violations

- Only 40/100 have trouble-free Wikipedia pages.

These warnings are publicly displayed on top of the page as either:

- Too much like advertising copy; and/or

- Written by someone too close to the firm.

The warnings look like this:

Please note that it gets worse when we go to the top 100 law firms where 59% of all firms either don’t have a page or have minor or major violations.

Why is Wikipedia so important to your web and social strategy?

Google treats Wikipedia as a really strong trust signal. Wikipedia has a very high domain authority, a sign of how well trusted it is by others.

So much so that Google ranks wiki pages very highly in its search results normally in the top one or two results. (Remember that the top two results will still normally get over 60% of all clicks.)

It often uses wiki as a trusted source for information in knowledge graph too which often boosts traffic much higher. That’s a story for another day.

Why is it so well trusted?

Because Wikipedia is a crowd-sourced version of the truth.

It’s not perfect: see for example the raging debate over who invented the telephone: you’re either Team Meucci or Team Graham Bell.

But in the internet age, Wikipedia is the closest thing we get to absolute truth.

How much does Google love Wikipedia?

Enough to buy its data and use it as the basis for its ongoing natural language programming work. Last decade, Google bought a copy of Wikipedia’s data called Freebase. It has redeveloped its search algorithms on the basis of that data.

What is Google trying to achieve by buying this data?

The only thing that Google cares about is producing the best results for you. It’s trying to perfect how it produces search results.

Search Google for ‘Christmas’ in March, and you’ll get a set of results about a Christian festival.

Search the same thing in November and you’ll likely get a recipe for making Christmas pudding.

Google’s improvements in search are a little like a world land speed record they comb the path and remove any objects that get in the way of an optimal performance. They think about user intent: what you want to achieve with your search.

A few years ago, Google knew that people had been gaming its algorithm, filling pages with keywords and such. So it set about changing the rules. The latest iteration of Google’s algorithm is almost impossible to game because it’s based on natural language.

What’s natural language programming?

NLP is where Google analyses literally every word and phrase on a page and tries to make sense of it a bit like a human would.

Part of the challenge of that is knowing what things are: concepts, objects, companies, animal, vegetable, mineral.

To make sense of the world, Google needs to understand semantic triples or RDF (Resource Description Framework): subject-predicate-object

According to Wikipedia:

The components of a triple, such as the statement “The sky has the color blue”, consist of a subject (“the sky”), a predicate (“has the color”), and an object (“blue”).”

What’s interesting here for us is understanding that to make sense of the world, Google needs to know what a subject is.

In our example, the subject is your law firm.

So my question for you is: does Google ‘know’ the name of your firm?

Possibly not.

As far as Wikidata is concerned, 39 of the top 100 law firms don’t ‘exist’ as entities or subjects. We know, of course, that they do in the real world it’s just that nobody among the 24,000+ active Wikidata users has bothered to tell them that the law firm Freeths exists.

This news is probably especially shocking to Freeths’ 844 employees (according to LinkedIn).

Is it easy to create yourself as a subject (aka an entity)?

The best thing to do is to get someone independent to create it for you and set it up with all the various attributes that you know are going to draw people towards you.

NB Do not create your own Wikipedia page. It is likely to get pulled down. You need to get an existing editor to do this for you. Here at TBD, we don’t create Wikipedia pages for people.

What you should also do is get someone independent to create your entity on Wikidata.

Wikidata how to start

So, in Freeths’ case, they might choose to include the fact that their name is Freeths, but that they also get called Freeths LLP. Oh, and that they used to be called Freeth Cartwright. And that their website is freeths.co.uk (but not freeths.com) and that they are headquartered in Nottingham. And add in their logo. And the fact that their LinkedIn address is https://www.linkedin.com/company/freeths-llp/ and so on.

Because then, when Google is trying to make sense of who on earth Freeths is, and Wikipedia is trying to source information about Freeths, it knows if people mean that specific organisation and not a competitor.

What are the benefits of getting this right?

Benefit number one: Web traffic to and from Wikipedia is huge.

Here are the top 10 firms’ Wikipedia pages traffic for 2019:

| Firm name | Wikipedia page views |

| DLA Piper | 131,653 |

| Clifford Chance | 98,488 |

| Hogan Lovells | 82,048 |

| Allen & Overy | 81,197 |

| Linklaters | 77,710 |

| Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer | 71,934 |

| Slaughter and May | 66,173 |

| Norton Rose Fulbright | 65,958 |

| CMS | 57,161 |

| Eversheds Sutherland | 55,802 |

As per usual, Slaughters outpunches its 14th place for revenue ranking by placing 7th in this list.

The real outperformers are, however, Mishcon and DWF who rank 12th and 13th for Wikipedia views and yet only 32nd and 22nd for revenues, respectively. (Mischon because of their work for Gina Miller on Brexit and DWF because of its listing on the stock exchange).

Views per employee top three firms

- Slaughter and May

- Harbottle & Lewis

- Dickson Minto

Dickson Minto’s rankings are surprisingly high in this table until you see that this is because there’s almost no information on them on their website – so readers are using Wikipedia as a proxy to find out more about them.

More stats

Only 34 of the top 100 firms are getting Wikipedia right at the moment. In the latest edition of The Digital 100, they get a perfect score.

At the other end, 37 firms are getting the lowest score possible with no Wikipedia and no Wikidata page.

The 29 in between have minor or major tweaks to make to improve both their standing on Wikipedia and on all their google results.

We provide more in-depth view of this in the latest edition of The Digital 100.

Benefit number two: Google’s algorithm trusts entities (law firms) with a wiki page and treats them to higher page rankings as a result

That means that, for a similar article to a competitors’ if you have a Wiki page and they don’t, then your article will most likely outrank theirs.

(And if you outrank theirs, you’ll get more traffic and more leads than them).

So, let’s say we search Google for £directors’ duties”. This is the result I get (yours may differ slightly depending on Google’s personalisation results). It’s drawn from Wikipedia.

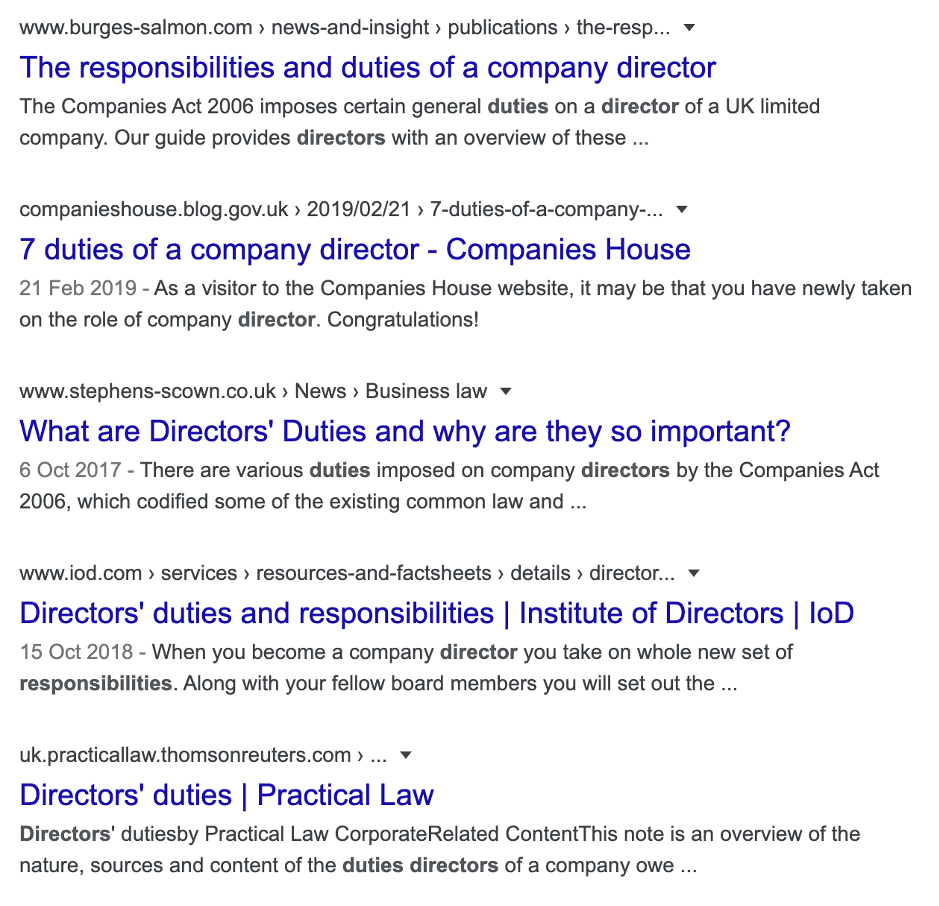

But it’s then quickly followed by these:

So, the first thing to note is that Wikipedia comes out top in the snippet. Snippets give people info before they click through to a page. Recent evidence points out that this produces less and less web traffic although it does put your content in front of more people.

Next, we’ll see that Burges Salmon outperforms both companies house and the IoD on this search. That’s quite the result. Finally, Stephens Scown appears in slot 3.

The content for BS and SS is similar enough as you’d expect. But Stephens Scown does not have a Wikipedia page. Is this the only reason it ranks lower? No. But despite using the precise phrase we’re searching for in comparison to Burges Salmon which does not use that phrase in the URL or H1, it underperforms its SW counterpart.

In Conclusion

Wikipedia is one part of your armoury to get higher web rankings and an independent view of your firm. If you’re not on there, you need to find a way of having your business promoted on there.

If you’d like to know how to get more of your thought leadership in front of people, then please contact us or subscribe to The Digital 100.